Twelve Principles of Native American Philosophy

1. WHOLENESS. All things are interrelated. Everything in the universe

is part of a single whole. Everything is connected in some way to

everything else. It is only possible to understand something if we

understand how it is connected to everything else.

2. CHANGE. Everything is in a state of constant change. One season

falls upon the other. People are born, live, and die. All things

change. There are two kinds of change. The coming together of things

I and the coming apart of things. Both kinds of change are necessary

and are always connected to each other.

3. CHANGE OCCURS IN CYCLES OR PATTERNS. They are not random or

accidental. If we cannot see how a particular change is connected, it

usually means that our standpoint is affecting our perception.

4. THE PHYSICAL WORLD IS REAL. THE SPIRITUAL WORLD IS REAL.

They are two aspects of one reality. There are separate laws which govern

each. Breaking of a spiritual principle will affect the physical

world and visa versa. A balanced life is one that honors both.

5. PEOPLE ARE PHYSICAL AND SPIRITUAL BEINGS.

6. PEOPLE CAN ACQUIRE NEW GIFTS, BUT THEY MUST STRUGGLE TO DO SO.

The process of developing new personal qualities may be called "true

learning."

7. THERE ARE FOUR DIMENSIONS OF TRUE LEARNING.

A person learns in a whole and balanced manner when the mental, spiritual, physical, and

emotional dimensions are involved in the process.

8. THE SPIRITUAL DIMENSION OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT HAS FOUR RELATED CAPACITIES:

* the capacity to have and to respond to dreams, visions,

ideals, spiritual teachings, goals and theories.

* the capacity to accept these as a reflection of our unknown

or unrealized potential.

* the capacity to express these using symbols in speech, art

or mathematics.

* the capacity to use this symbolic expression towards action

directed at making the possible a reality.

9. PEOPLE MUST ACTIVELY PARTICIPATE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THEIR OWN POTENTIAL.

10. A PERSON MUST DECIDE TO DEVELOP THEIR OWN POTENTIAL.

The path will always be there for those who decide to travel it.

11. ANY PERSON WHO SETS OUT ON A JOURNEY OF SELF-DEVELOPMENT WILL BE AIDED

. Guides, teachers, and protectors will assist the traveler.

12. THE ONLY SOURCE OF FAILURE IS A PERSON'S OWN FAILURE TO FOLLOW THE TEACHINGS.

~source

Primal Religions

Huston Smith characterizes both African and native North and South American religions as "primal", or alternatively, "tribal". These primal religions are far older than the so-called "historical religions" that have supplanted them in many parts of the world. Primal religion is "the religion of peoples who live in small communities, on subsistent economies that are the direct product of their own efforts, and without depending on writing". (Smith 365) Primal religion is now found only in parts of "Africa, Australia, Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, Siberia, and among the Indians of North and South America." (ibid)

The following are some important differences between primal and modern religions and world-views:

1. Unlike modern societies, tribes feature relatively little division of labor. Tribes typically do differentiate between the tasks of men and women, but they don’t distinguish between clergy and laity, or between sacred and secular, human and animal, animate and inanimate. In that sense, the tribal world is unfragmented. Tribal people are embedded in the natural world around them, and that whole world partakes in the sacred. Because primal religions see humans at one with nature, and all nature as sacred, primal religions revere all aspects of the natural world. There is little distinction between the individual and the tribe, or between the tribe and its environment, or between the human and the non-human. There is no metaphysical hierarchy of being in terms of which humans are "higher" or "better" than animals or plants or even rocks; every individual thing is alive and important. Animals and plants are usually thought of as "people" too. Hence there is no distinction between religious and non-religious activities: every interaction with the world has religious significance. Primal religions celebrate nature in the cycle of the seasons, and often in totemism (the symbolic joining of a tribe or clan with an animal species).

2. Primal religions assume a single reality, which includes two kinds of being, and thus can be experienced in two different ways. One sort of being is temporal, and is the stuff of "normal" experience of the world. Temporal beings go in and out of being; the seasons change, people are born and die. The second sort of reality includes unchanging entities which are always potentially present in ordinary experience. Humans can partake in the immortal and give significance to their lives by ritually re-creating eternal archetypal patterns. For the Aborigines and Native Americans the normally unseen world is populated by eternal archetypes of not only things (the man, the woman, the fish, the wolf, the eagle, the bear, etc.) but also activities (hunting, lovemaking, war). An individual in the temporal world can partake of eternity by identifying completely with the archetypes in daily life: by "becoming" not a hunter or warrior but the Hunter or the Warrior. The Aborigines call these states of ritual identification "the Dreaming"; they are the closest thing to "worship" that we find in Aborigine culture. Primal religions frequently use natural hallucinogens and other drugs (alcohols, mushrooms, peyote, cannabis, mescaline, cocaine) to facilitate this identification with the archetypes. For example, Castaneda "becomes" The Crow only while tripping.

3. Primal cultures are oral cultures; they have no tradition of literacy. The "texts" of primitive religions are myths, which are transmitted orally. "Oral transmission" includes drama and spectacle in addition to simple storytelling. Since primal peoples cherish their ancestors (who are thought to be closer to the primal Source of being), they have the highest respect for the myths given to them by their ancestors, and they treat the myths with the utmost respect, memorizing them carefully, and repeating them often. The myths contain not only stories of archetypal heroes, but specific instructions for hunting, gathering, building houses and boats, cooking, preparing medicines, etc., so memorizing them correctly is important for the continued well-being of the tribe. According to Smith, orality is important for primal religion because it keeps primitive people focused on their own experience of the world. Sacred texts cannot assume undue importance; oral cultures can still "sense the sacred through nonverbal channels" (Smith 370). Orality ensures that primal peoples do not fill their heads with endless trivia; if something is learned, it is used or it is forgotten. Orality also protects primal people from over-valuing thought itself (a tendency of the lettered, according to Smith).

4. Primal religions value individuality; they see the uniqueness of things and places. One bird is not interchangeable with another. One corner of the room might be more suitable for sitting in than another; and the same corner might not be suitable for me and for you. (Don Juan tells Castaneda to find the place in the room that feels right for him.) One man’s house is not interchangeable with another’s. You cannot uproot a person from one place and expect that she will necessarily thrive elsewhere. A human is not like a machine that needs only electricity to run well, that can be transported anywhere and just plugged in. A human is not like an angel, a pure intellect that can flourish no matter where it lives or what it is nourished by. Animals and humans are much more like plants; they thrive in some habitats but not in others.

5. Primal nature rites focus mainly on maintaining the regular course of natural events. The rites do not try to force nature to do anything supernatural; rather, the tribe seeks merely that rainfall and temperature and local wildlife supply stay normal. This cooperative orientation toward nature makes primal peoples essentially conservative about making large-scale alterations to the natural world that would upset nature’s norms or damage individual plants and animals, e.g., dams, cities, highways, etc. Indeed, they are conservative about small alterations. Environmentalists often look to primal peoples as models of proper human interaction with nature.

6. The natural world and the body are valued in primal religious thought, unlike in most historical religions. Thus there is little interest in escaping the body or despising the world. As Smith says, "Primal peoples are ... oriented to a single cosmos, which sustains them like a living womb. Because they assume that it exists to nurture them, they have no disposition to challenge it, defy it, refashion it, or escape from it. It is not a place of exile.... Its space is not homogeneous; the home has a number of rooms, we might say, some of which are normally invisible. But together they constitute a single domicile. Primal peoples are concerned with the maintenance of personal, social, and cosmic harmony, and with attaining specific goods – rain, harvest, children, health – as people always are. But the overriding goal of salvation that dominates historical religions is virtually absent from them, and life after death tends to be a shadowy semi-existence in some vaguely designated place in their single domain." (377)

7. Primal religions appear on the surface to be polytheistic, but in fact usually suppose one High God or Ultimate Power or Supreme Being. But the High God is often not named or even spoken of directly; it is assumed unknowable. Naming the High God would also conceptually separate that God from the world, thus draining some of the holiness from the ordinary world, since the conceptual separation makes clear that the world is not the High God (yet in the primal view, it is). The ordinary world is thought to be obviously a manifestation of the Great Power. Obviously, to the primal mind, the world of the senses is not the whole story. That sensible world signifies; it can be only if there is something More. Nothing is merely as it appears; rather, everything is symbolic, "transparent" to its divine source.

Western philosophers find the primal approach intriguing but problematic, especially in its rejection of ordinary metaphysical categories. But there lies its attraction for other Western minds. Curious reversals abound. In the American colonial times and through the 19th century, white Americans were fascinated with the natives. "Indian captivity narratives" were a popular literary form, e.g., James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. The popular captivity narratives usually pictured native Americans as cruel savages (e.g., Ethan Allen’s accounts) in order to build popular support for the expansionist goals of the young America. But in fact as early as the 16th century, captured Europeans often voluntarily rejected their culture to live with Native American tribes; Daniel Boone was the most famous example. The hero of the recent film Dances with Wolves is another. Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1753: "When white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and have lived a while among them, tho’ ransomed by their Friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay ... yet in a Short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good Opportunity of escaping again into the Woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them."

Nowadays, as Richard Rodriguez points out, native Guatemalans embrace Mormonism while "blond animal-rights activists in Orange County are becoming the new pantheists, California’s new tribe of Indians – proclaiming the equality of all living things."

~source

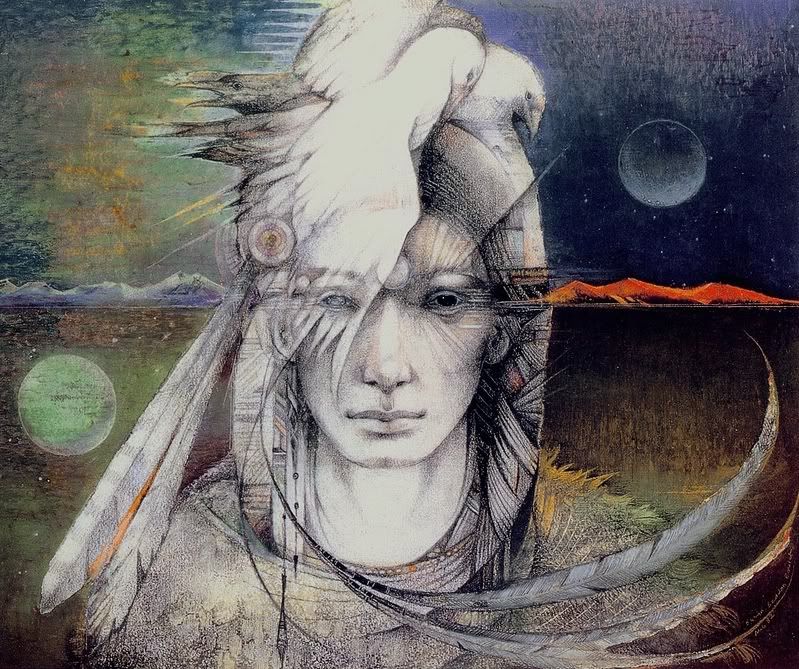

Paintings By: Susan Seddon-Boulet

Content from Soil Sex Third Eye Star

Additional Programming by DPC