J. Krishnamurti

ATHENS, GREECE 1ST PUBLIC TALK 24TH SEPTEMBER 1956

Question: What makes up a problem? And is any problem solved by dissecting it and finding its cause?

Krishnamurti: What is a problem? Please do not just wait for an answer from me. You are not merely listening to someone talking, but we are trying to find out together what creates a problem. You each have your own problems. How do they come into being?

We have contradictory desires, do we not? I want to be rich, let us say, and at the same-time I know or have heard that wealth is detrimental to the discovery of truth. So there is a contradiction in my desires - the contradiction of wanting and not wanting. It is this conflict of contradictory desires in us that creates a problem, is it not? We have many contradictory desires, many conflicting pursuits, ambitions, urges, and all these contradictions create a problem. Now, can the mind ever resolve the problem of self-contradiction by imposing one desire on another?

Take hatred, for example. What causes hatred? Surely, one of the biggest factors is chauvinism; another is the sense of superiority or inferiority created by economic differences; still another is the division created between man and man by what are called religions. These are the principal causes of hatred, and they give rise to many other major problems in the world today. Knowing all this, can the individual free himself from hatred? This is where our difficulty lies, and if you will listen carefully I think you will see it.

When I say "I know the cause of hatred", what do I mean by the words "I know"? Do I know it merely through the word, the intellect, or do I know it with the totality of my being? Am I aware of the root of hatred in myself, or do I know its cause only intellectually or emotionally? If the mind is totally aware of the problem, then there is freedom from the problem; but I cannot be aware of it with the totality of my being if I condemn the problem. It is very difficult for the mind not to condemn; but to understand a problem there must be no condemning of that problem, no comparing of it with another problem.

I do not think we realize that we are all the time either condemning or comparing. Let us not try to excuse ourselves, but just watch our daily life, and we shall see that we never think without judging, comparing, evaluating. We are always saying "This book is not as good as the other one", or "This man is better than that man; there is a constant process of comparison, through which we think we understand. But do we really understand through comparison? Or does understanding come only when one ceases to compare, and just observes? When your mind is integrated, you have no time to compare, have you? But the moment you compare, your attention has already moved elsewhere. When you say "This sunset is not as beautiful as that of yesterday", you do not really see the sunset, for your mind has wandered off to the memory of yesterday.

When the mind is capable of not condemning, not comparing, but merely examines the problem, then surely the problem has undergone a fundamental change; and then the problem ceases. Simple awareness is enough to put an end to the problem.

What do we mean by awareness? If you observe your own mind you will see that it is always comparing, judging, condemning. When we condemn or compare, do we understand? If we condemn a child, or compare him with his brother, obviously we do not understand him. So, can the mind be simply aware of a problem, without condemning or comparing? This is extremely difficult, because from childhood we have been brought up to condemn and to compare. And can the mind cease to condemn and compare without being compelled? Surely, when the mind sees for itself that to condemn or to compare does not bring about understanding, then that very perception frees the mind from all condemnation and comparison. This means a complete separation of the mind from all traditions and beliefs.

To free one's mind in this deep sense requires a great deal of insight, because the mind is very easily influenced. It is always seeking security, not only in this world, in society, but also in the so-called spiritual world. If you go into the whole process of your own mind, you will see that this is so; and a mind that is seeking security can never be free.

To observe the total process of the mind without condemnation or comparison, to be conscious of it without judgement,to recognize and understand it from moment to moment - this is awareness, is it not?

You have listened to what is being said, and probably you either approve or disapprove of it, which means that you accept or reject it. But we are not just dealing with ideas, which can be accepted or rejected; we are not putting new ideas in the place of old ones. We are concerned with the totality of the mind, the totality of yourself, of your whole being, which cannot be approached through ideas. Please do not accept or reject, but try to find out, as you listen, how your own mind is operating. Then you will see that the mere observation of the process of the mind is in itself sufficient to bring about a fundamental transformation within the mind.

We see that there must be in us a radical change, and we think that we have to make an effort to bring it about. But any effort in that direction is merely another form of wanting a result, so we are back again in the same old process. What is necessary, surely, is not more control, more knowledge, but rather awareness of the totality of oneself, without any sense of condemnation or approval. Then you will find that the mind is renewed and absolutely still. For this an exceptional amount of energy is required; but it is not energy spent in the usual way, on comparison, on suppression, on the imposition of discipline, nor is it the energy acquired through prayer. It is the energy that comes with full attention. Every movement of thought in any direction is a waste of energy, and to be completely still the mind needs the energy of absolute attention. When the mind is alert, aware, wholly attentive, it becomes very quiet, very still; and only then is it possible for that which is immeasurable to come into being.

September 24, 1956

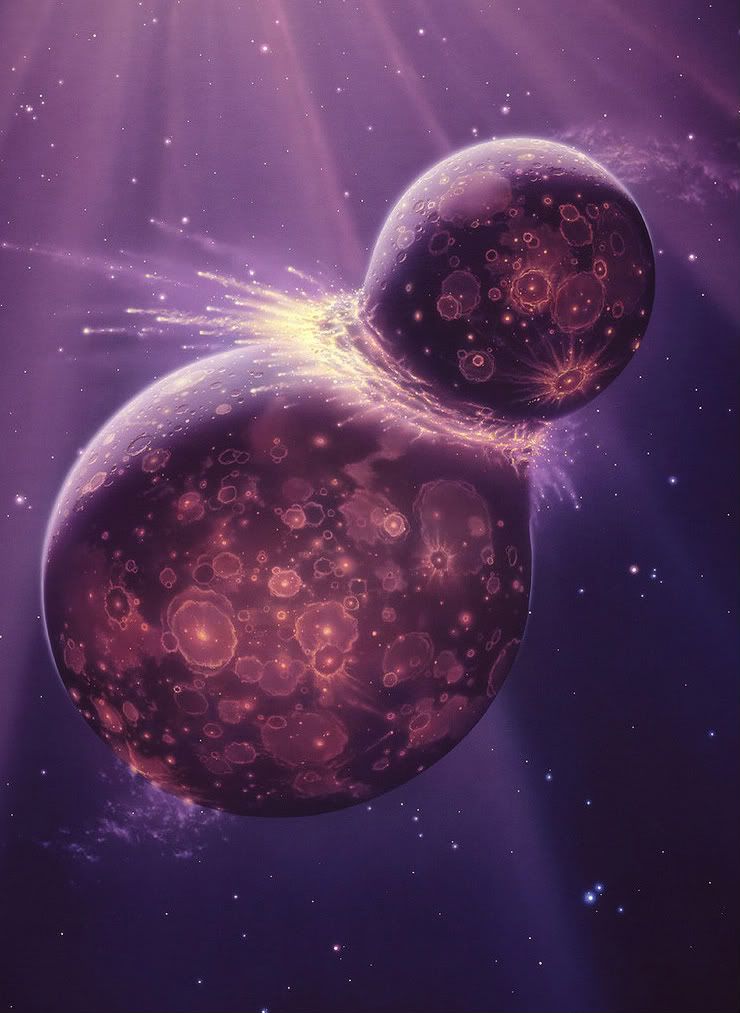

{Images Linked/Art by Joe Tucciarone/Programming by DPC}

[Page vi]

THE LORD BUDDHA HAS SAID

...that we must not believe in a thing said merely because it is said; nor traditions because they have been handed down from antiquity; nor rumors, as such; nor writings by sages, because sages wrote them: nor fancies that we may suspect to have been inspired in us by a Deva (that is, in presumed spiritual inspiration); nor from inferences drawn from some haphazard assumption we may have made; nor because of what seems an analogical necessity; nor on the mere authority of our teachers or masters. But we are to believe when the writing, doctrine, or saying is corroborated by our own reason and consciousness. "For this," says he in concluding, "I taught you not to believe merely because you have heard, but when you believed of your consciousness, then to act accordingly and abundantly."

(Secret Doctrine, Vol. III, page 401.)